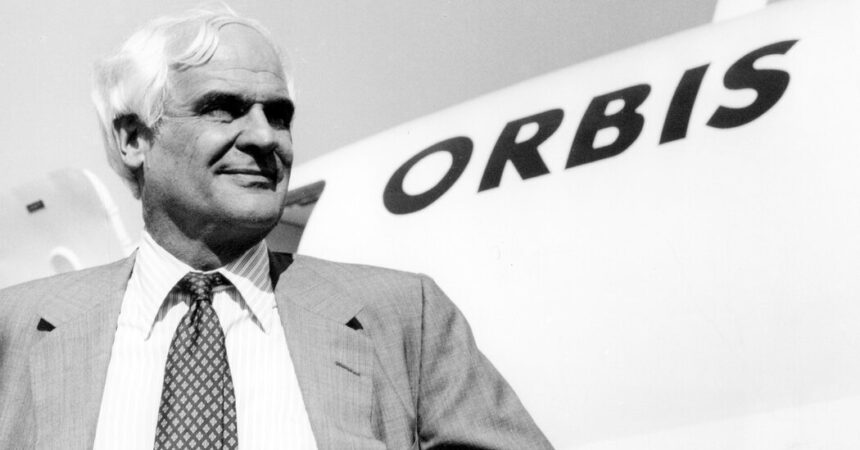

David Paton, an idealistic and innovative ophthalmologist who converted a United Airlines plane into a flying hospital that toks to developing countries to operate patients and educate local doctors, died on April 3 at home, Nevada. He was 94 years old.

His death was confirmed by his son, Townley.

Son of a prominent ocular surgeon in New York whose patients included the SHA of Iran and the Financial J. Pierpont Morgan’s Horse, Dr. Go. Paton (pronounced Ton-Ton) was teaching in the Wilmer Eye Institute of the Johns Hopkins University in the early 1970s, when it was discouraged by increasing the cases of prevention blindness in remote places.

“More doctors of the eyes were needed,” he wrote in his memoirs, “Second view: views of the odyssey of an eye doctor” (2011), “but it was equally important was the need to be the medical education of existing doctors.” “

But how?

The shipping trunk considered equipment, almost as a circus would, but that presented logistics challenges. He reflected the possibility of using a medical ship like the one that the Hopper Humanitarian Group project sent to everyone. That was too slow to him.

“Shortly after the first landing of the Moon in 1969, to think that Big was becoming a reality,” Dr. Paton wrote.

And then, a moon idea hit him: “Could it be a plane to be the answer? A large enough plane could convert an operational theater, a teaching classroom and all the necessary facilities.”

All Hey needed was a plane. Hello, he asked the military to donate one, but that was not a stress. He approached several universities for money to buy one, but the administrators rejected it, saying that the idea was not feasible.

“David was willing to risk others,” said Bruce Spivey, founding president of the American Academy of Ophthalmology, in an interview. “He was lovely. He was inspiring. And he did.”

Dr. Paton decided to raise funds on his own. In 1973, the founded Orbis Project with a group of rich and well -connected society figures such as Texas Leonard F. McCollum and Betsy Trippe Wainwright, daughter of founder Pan American World World Airways, Juan Trippe.

In 1980, Mr. Trippe helped persuade Edward Carlson, executive director of United Airlines, to donate a Jet DC-8. The United States Agency for International Development contributed $ 1.25 million to convent in a hospital with an operating room, a recovery area and a classroom equipped with televisions, so that local medical workers could monitor surgeries.

The surgeons and nurses offered their services as volunteers, agreeing to pass two to four weeks abroad. The first flight, in 1982, was for Panama. The plane then went to Peru, Jordan, Nepal and beyond. Mother Teresa once visited. The Cuban leader Fidel Castro did so.

In 1999, London’s Times magazine sent a journalist to Cuba to write about the plane, now known as the Flying Eye Hospital. One of the patients who arrived was a 14 -year -old girl named Julia.

“In developed nations, Julia’s condition would have been little more than an irritation,” said The Sunday Times. “It is almost certain that it had uveitis, an inflammation inside the eye, which can be eliminated with drops. In Great Britain, cats are equally treated easily.”

His doctor was Edward Holland, a prominent eye surgeon.

“Holland uses small knives to make an opening that allows you to carry your instruments in the eyes, and is soon pulling Julia’s scar tissue,” said Sunday Times. “As the fabric is removed, a dark and liquid student is revealed, without being seen for a decade. It is an intimate and mobile moment; this is the music of the camera of medicine. Then, it breaks and eliminates the cataract and implants a lens to attend it.”

Cuban ophthalmologists observed in the observation room applauded.

But after surgery, Julia couldn’t see yet.

“And then a minor miracle begins,” the article continued. “As the swelling begins to fall, she makes discoveries about the world around her. Minute by minute can see something new.”

David Paton was born on August 16, 1930 in Baltimore, and grew up in Manhattan. His father, Richard Townley Paton, specialized in corneal transplants and founded the eye bank for the restoration of the view. His mother, Helen (MESSERVE) Paton, was an interior designer.

In his memoirs, Dr. Paton described growing “among fine and intellectual people, widely traveling from the establishment.” His father practiced in Park Avenue. His mother launched parties at his home at the Upper East Side.

David attended the Hill school, a boarding school in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, there with James A. Baker III, a Texan who later became Secretary of State for President George Hw Bush. They were roommates at Princeton University and the best friends in a lifetime.

“David came from a very privileged environment, but he had his feet on the ground and only a very pleasant guy,” Baker said in an interview. “I had objectives in heterosexual life. He was a student much better than me.”

After graduating from Princeton in 1952, David obtained his medical degree at Johns Hopkins University. He worked at high -level positions at the Wilmer Eye Institute and served as president of the Department of Ophthalmology of Baylor College of Medicine de Houston.

In 1983, he became the medical director of the King Khaled Eye Specialist hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

“Among my duties,” he wrote in his memoirs, “I was providing ocular attention to many of the princesses and princesses of the kingdom, around 5,000 of each, it was tolerant, and it seemed that everyone insisted on being treated exclusively by the doctor.”

Brown by Dr. Paton to Jane Sterling Treman and Jane Franke ended up divorce. He married Diane Johnston in 1985. She died in 2022.

In addition to his son, three steps survive, Garrison Franke, James Beardmore and Lauren Ivanhoe; Two grandchildren; And a granddaughter passing.

Dr. Paton left his role as a medical director of the Orbis project in 1987, after a dispute with the Board of Directors. That year, President Ronald Reagan awarded the Medal of Presidential Citizens.

Althegh, his official connection with the organization was over, occasionally served as an informal advisor.

Now called Orbis International, the organization is on its third plane, a MD-10 donated by Federal Express.

From 2014 to 2023, Orbis made more than 621,000 surgeries and procedures, according to its annual report more recently, and offered more than 424,000 training sessions for doctors, nurses and other suppliers.

“The plane is such an unique place,” Dr. Hunter Cherwek, vice president of clinical services and clinical technologies of the organization said in an interview. “It was simply an incredible bold and visionary idea.”