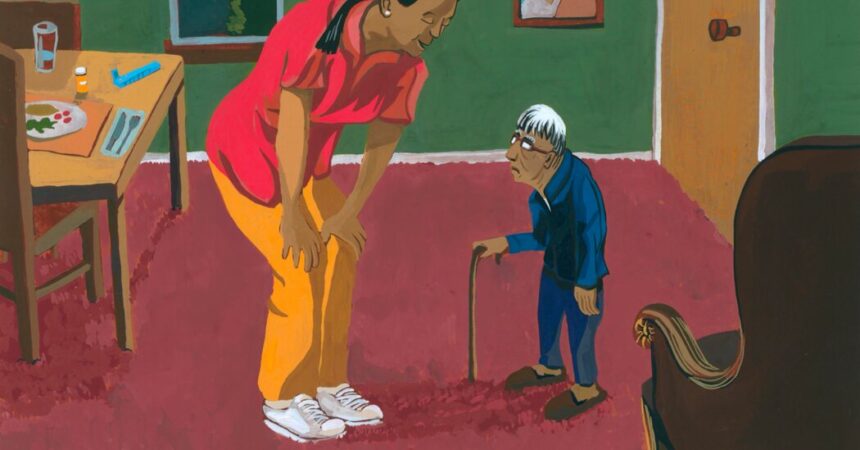

An excellent example of Elderspeak: Cindy Smith was visiting her father in her assisted life apartment in Roseville, California. An assistant who was trying to induce him to do something: Mrs. Smith no longer remembers exactly what, “let me help you, love.”

“He simply looked at him, under his bushy eyebrows, and said:” What are we going to marry? “” Remember Mrs. Smith, who laughed well, she said.

His father was 92 years old, a retired county planner and a veteran from World War II; The macular degeneration had reduced the quality of his vision and used a walker to move, but remained cognitively acute.

“Hey, it would not usually get too frozen with people,” said Smith. “But he made the feeling that he was an adult, and was always treated as one.”

People almost intuitively understand what “Elderspeak” means. “It is a communication for older adults who sound like talking about babies,” said Clarissa Shaw, a dementia care researcher at the Faculty of Nursing at the University of Iowa and co -author of a recent article that helps researchers document their use.

“It arises from a frilician, incompetence and dependence ageneist assumption.”

Its elements include inappropriate love. “Elderspeak can be a controller, a little mandon, so to soften that message is” Honey “, Dearie”, “Sweetie,” said Kristine Williams, a gerontologist nurse from the Nursing School of the University of Kansas and another co -author.

“We have negative stereotypes or older adults, so we change the way we talk.”

Or caregivers can resort to plural pronouns: Are we ready to take our bath? There, the implication “is that the person cannot act as an individual,” said Dr. Williams. “Hopefully, I don’t go to the bathroom with you.”

Sometimes, Anca thickness use a stronger volume, shorter sentences or simple insulted words. Or they can adopt an exaggerated and tight vocal quality more suite to the presenters, along with words such as “go to the bathroom” or “Jammies”.

With the so -called label questions It’s time for lunch now, right? – “He is asking them a question, but not letting them answer,” explained Dr. Williams. “It tells you about how to answer.”

Studies in nursing homes show how common this speech is. When Dr. Williams, Dr. Shaw and his team analyzed the video recordings of 80 interactions between staff and residents with dementia, discovered that 84 percent had involved some form of Elderspeak.

“Most Elderspeak are well intentional. People are trying to show them,” said Dr. Williams. “They don’t realize the negative messages that appear.”

For example, among the residents of elderly with dementia, studies have found a relationship between exposure to the width and behavior known collectively as resistance to attention.

“People can get away, cry or say no,” explained Dr. Williams. “They can close their mouths when you try to feed them.” Sometimes, they push caregivers or hit them.

She and her team developed a training program called Chat (for Changing Talk), three -hour sessions that include communication videos between staff and patients, aimed at reducing the Elderspeak.

It worked. Before training, in 13 elderly homes in Kansas and Missouri, almost 35 percent of the time spent on interactions consisted or Elderspeak; That number was only around 20 percent later.

At the same time, resistant behaviors represented almost 36 percent of the time dedicated to meetings; After training, that proportion fell to about 20 percent.

A study conducted in a west hospital, again between patients with dementia, found the same type of decrease in resistance behavior.

In addition, chat training in elderly homes was associated with lower use or antipsychotic medications. He thought that the results did not reach statistical significance, due in part to the small sample size, the research team considered them “clinicularly significant.”

“Many of these medications have a black cash warning of the FDA,” said Dr. Williams about drugs. “It is risky to use them in fragile older adults” due to their side effects.

Now, Dr. Williams, Dr. Shaw and his colleagues have simplified Chat’s training and adapted it for online use. They are examining their effects in approximately 200 elderly homes throughout the country.

Even without formal training programs, individuals and institutions can fight Elderspeak. Kathleen Carmody, owner or senior matters of home care and consulting in Columbus, Ohio, warns his assistants who are addressed to customers as Mr. or Mrs. or Ms., “Unless or until they say,” Call me Betty. “

However, in the long -term care, families and residents can worry that correcting the way personnel members speak could create antagonisms.

A few years ago, Carol Fahy was furious about the way assistants in an assisted life center in the Cleveland suburbs treated their mother, who was blind and had a bee encouraged in its 80 years.

Calling it “Honey” and “Honey Babe”, the staff “would move and lulled, and put their hair in two pigtails on their head, as it would with a Toppeler,” said Mrs. Fahy, 72, a psychologist in Kanehehe, Hawaii.

Althegh recognized the ‘credible intentions of the assistants, “there is a falsehood in this regard,” he said. “It doesn’t make someone feel good. It’s real alienating.”

Mrs. Fahy considered the discussion of her objections with the assistants, but “I did not want them to take reprisals.” In all, for several reasons, he transferred his mother to another installation.

However, opposing Elderspeak does not need to be an adversary, said Dr. Shaw. Residents and patients, and people who meet Elderspeak elsewhere, because it is barely limited to medical care environments, they can politely explain how they prefer to be spoken and how they want to be called.

Cultural differences also come into play. Felipe Agudelo, who teaches health communications at the University of Boston, said in certain contexts, a tiny or misleading “does not come from underestimating her intellectual capacity. It is a term of affection.”

He emigrated from Colombia, where his 80 -year -old mother was not offended when a doctor or health worker asks him to “take the pastillite” (take this little pill) or “move the little hand” (move the little hand).

That is usual and “she feels that she is talking to someone who cares,” said Dr. Agudelo.

“Come to a negotiation place,” he advised. “It doesn’t have to be challenging. The patient has the right to say:” I don’t like you talk to me that way. “

In return, the worker “must recognize that the recipient cannot come from the same cultural background,” he said. That person can answer: “This is the way I usually speak, but I can change it.”

Lisa Greim, 65, a writer withdrawn in Arvada, Colorado, withdrew against Elderspeak recently when she enrolled in Medicare’s drug coverage.

Suddenly, he told an email, a pharmacy of orders by mail began to call almost daily because he had filled a recipe as expected.

These people who call “gentilly condescending”, apparently reading of a script, everyone said: “It’s hard to remember taking our medications, right?” – As if they were swallowing pills together with more. Greim.

Annoyed by his presumption, and his follow -up question about how often he forgot his medications, Mrs. Greim informed them that having supplied before, she had enough supply, thanks. She would reorder when she needed more.

Then, “I asked them to stop calling,” he said. “And they did.”

The new old age occurs through an association with Kff Health News.