This article is part of OverlookedA series of affectionate about notable people whose deaths, from 1851, were not reported in the times.

Joyce Brown’s New York minute yearned more than most. A time secretary, Brown was homeless in 1986 and Been Begen in a heating grid at Second Avenue and 65th Street in Manhattan.

It spent a year or so before the city officials collected it, involuntarily committed to a psychiatric hospital, where it was declared medications with mentally sick and forced diseases. Brown, better known as Billie Boggs, was the first homeless person to become the focus of the newly expanded initiative of Mayor Edward I. Koch to address the growing visibility of the lack of housing and mental illnesses not treated in the streets.

But, as she would say later in the interviews, the city chose “the wrong.” Unlike the boxes more or less, other people who would face similar destinations, said he knew his rights and that he would begin to exercise them the next day.

What followed was a historical demand focused on mental health, civil freedoms and involuntary psychiatric treatment of homeless. “I’m not crazy,” Brown said. “Only homeless.”

In a short time, Brown was elevated from the pavement to prominence, with a whirlwind of interviews on talks and news programs.

When Brown died of a heart attack on November 29, 2005, at 58, for a long time he had been forgotten.

But the repercussions of its transient fame still resonate on the sidewalks and the city of the city, such as the government. Kathy Hochul and Mayor Eric Adams have introduced their own initiatives to address the lack of housing in New York, including involuntary hospitalization of people in the psychiatric crisis.

Joyce Patricia Brown was born on September 7, 1947 in Elizabeth, NJ, the youngest of six children, most of whom were born in South Carolina and Florida.

His father, William Brown, told the census enumerators in 1950 that he was employed. His mother, Mae Blossom Brown, worked on factory assembly luggage.

Some time after graduating from high school, Joyce Brown worked as Secretary of the Elizabeth Human Rights Commission, where he could have learned one or two things about his own constitutional privileges. He also worked as Secretary for the mayor of Elizabeth at that time, Thomas G. Dunn, and for Thomas & Betts, a manufacturer of electrical equipment, chrowing a death warning of Nesbitt funeral home in Elizabeth.

At 18, he thought, he was addicted to cocaine and heroine and was stealing money from his mother. His mother died in 1979, which, according to his relatives, could have caused a more emotionally descending spiral.

By 1985, she had lost work. He turned to live with his sisters in New Jersey and was treated with letters in clinics and hospitals. The efforts of her sisters to help her resulted in arguments, and in 1986 she moved to Manhattan, where she made her home on the sidewalk near a Swensen ice cream at the top of this, urinating and defining outdoors nearby.

She adopted the name of Billie Boggs, a twisted tribute to Bill Boggs, a television presenter in Wnew (now Wnyw), with whom she had been haunted.

For some regular neighbors and passersby, it became a part of New York, the child who does not find in the guides; Converse with her about the news. For others, she was a threat: curse and shout racial epithets, partly black men and even hit people.

His sisters sought to have her hospitalized. But doctors said he did not show a danger to herself and released her.

On October 12, 1987, after having monitored the legs for months under a Koch administration strategy known as the project aid (the initials represented for the homeless emergency link project), aimed at eliminating the homeless people with severely mental mental illnesses of Focy falsified and forced, the drug emergency hospital and the Bellevue hospital, where it was admitted and injected with Treansets.

The next day, according to an article in 1988 in the New York magazine, he called the Union of Civil Liberties in New York from a public telephone in the hospital. Norman Siegel, executive director of the organization, was one of the lawyers assigned to his case. In the Court, a Bellevue psychiatrist presented a diagnosis or “chronic paranoid schizophrenia.”

That night, one of her sisters recognized her from a sketch in the court room in television news.

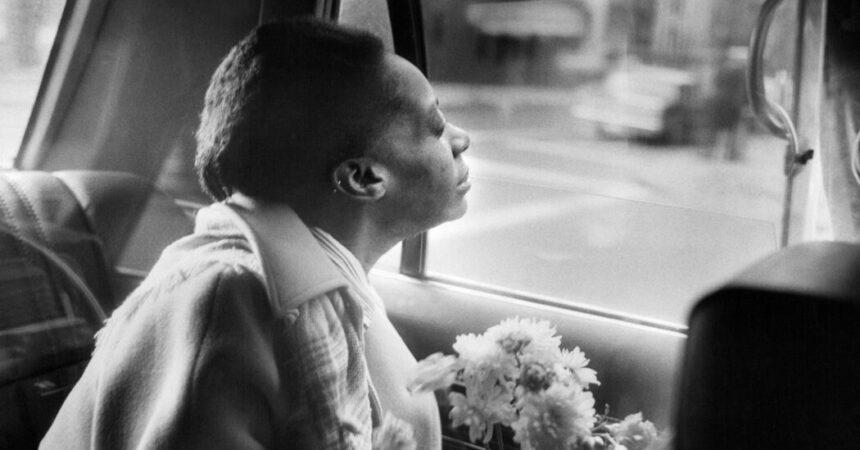

That image was in a marked juxtaposition to a photograph produced by Re -Family, which showed a smiling brown, with a red dress and golden earrings when it was hugged by a man with an tuxedo with a pink loop tie, his sisters smiling towards the nearby camera.

“This used to be my sister,” one of the sisters told Newsday. “This used to be us.”

A judge of the State Supreme Court ruled that Brown “was not unable to take care of her essential needs” and ordered her to release her, but she remained in Bellevue while the city appealed the decision. The city won the appeal, but after a subsquented appeal of Brown’s lawyers, a judge ruled that he could not be mediated by force. That appeal was withdrawn when Bellevue liberated Brown, saying that it made no sense in his remaining if he could not receive the hospital’s attention. A total of 84 days had passed there.

It soon became a media star, a symbol of justice that, according to their lawyers, presented themselves in their lucid and articulated interviews as a more or less rational example of urban Vortocratation that, he said, “under surveillance” for months “like me” “”

“In a civilized society, you not only pick up people against their will and take them to the hospital when they are only for a mayor program,” he told Morley Safer for a 1988 segment of the CBS news. “” All this is political. I am a political prisoner due to Mayor Koch. “

In the same segment, Mayor Koch insisted that defecating in the street was “strange” and said that Brown’s ability to speak jointly in the camera demonstrated the effectiveness of his hospitalization and the medication they had given him.

That year, Brown also appeared in “The Phil Donahue Show”, after being equipped with Bloomingdale’s, and delivered a conference to a forum of the Harvard Law Faculty in which he sacrificed “a view of the street” or homeless. The sacrifices of books and films flooded the officials of the Union of Civil Liberties of New York. The Associated Press called it “the most famous homeless person in the United States.” At his Moscow summit with Mikhail S. Gorbachev, the Soviet leader, in 1988, President Ronald Reagan invoked his case as an example of freedom in contrast to Moscow’s policy to stop political dissidents by claiming that they are mentally ill.

“Instead of talking about me, why doesn’t the president help me obtain permanent homes?” Brown was summoned by saying.

Following Brown’s case, the Help project faced public scrutiny and criticism. The impulse of the program stagnated, and was possible discontinued. Brown’s demand continues to serve as a precedent in debates on mental health, lack of housing and civil freedoms.

After Brown was released, he worked briefly as secretary of the Union of Civil Freedoms. But he resigned because, he said, he wouldn’t like work.

“The courage he had always dissipated,” Siegel said about her in an interview.

She put weight; His march slowed; She could have a medical leg again for a while. Around 1991, she moved to a supervised group house for homeless women formally, but also returned to the streets for Panhandle, saying that her sisters had delayed the return of more than $ 8,000 in Social Security checks. She continued to live with $ 500 a month in disability payment and avoided the press.

When Brown was initially released from Bellevue, it was against the recommendation of two judges of the State Supreme Court. “We can approach time,” they wrote, “when the problem of homeless people will face sincere and realistic attitudes and resources.”

“Now,” said Siegel, “35 years later, the hopes of dissident judges unfortunately have not yet materialized.”